Back to home

Back to homeLast updated Dec 4 2025

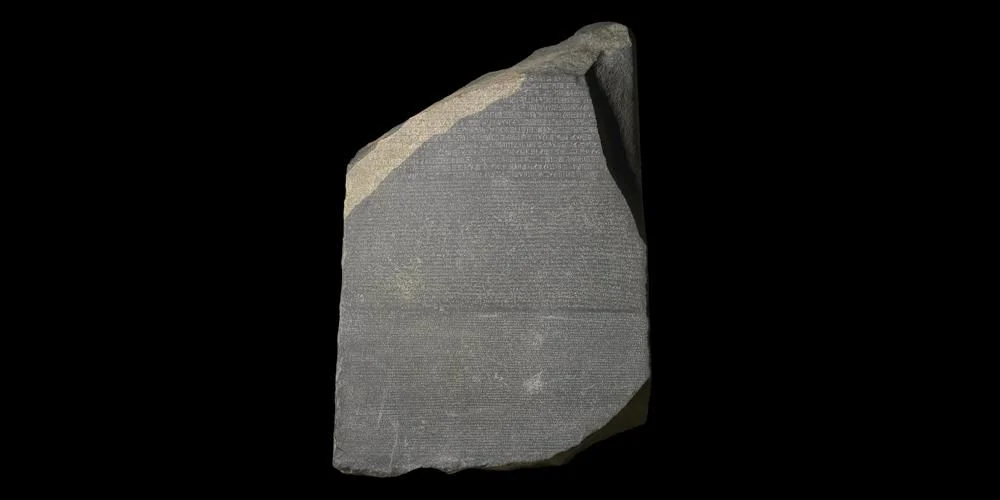

Discover 2 million years of human history in just 60 minutes. This guide covers the British Museum's absolute must-sees, from the Rosetta Stone to the Parthenon Sculptures. Avoid the overwhelm of 8 million objects and focus on the 10 most significant treasures that defined civilizations from Ancient Egypt to Medieval Europe.

Planning your The British Museum visit?

Your simple audio guide to the 10 must-see masterpieces

Ancient Egyptian scribes

Carved in 196 BCE, this granodiorite stele was key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. It displays the same decree in three scripts: hieroglyphic, Demotic, and ancient Greek, allowing Jean-François Champollion to crack the code in 1822. Discovered by Napoleon's soldiers in 1799, it remains the museum's most visited object.

Listen to our audio tour sample

"Discover the secrets behind Rosetta Stone and other masterpieces."

Free Audio Tour

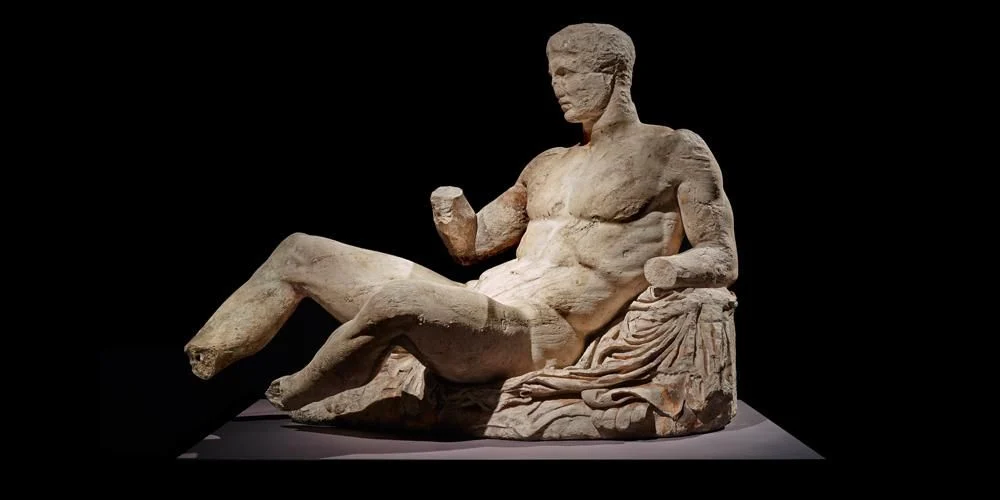

Phidias and workshop

Created around 447-432 BCE for the Parthenon in Athens, these marble sculptures represent the pinnacle of classical Greek art. Removed by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s, they revolutionized European art with their lifelike forms. Despite ongoing controversy regarding their return to Greece, they remain a breathtaking display of ancient mastery.

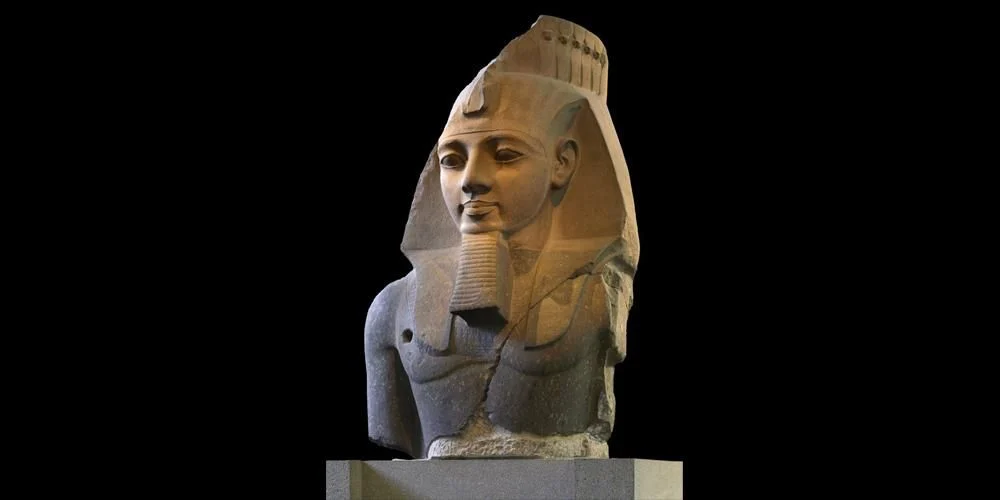

Ancient Egyptian sculptors

This 7.5-ton granite head portrays Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt for 66 years (c. 1279-1213 BCE). Once part of a massive statue at the Ramesseum, its serene expression conveys absolute royal power. Transported to London in 1818, this masterpiece inspired Shelley's famous poem 'Ozymandias' and symbolizes the grandeur of ancient Egypt.

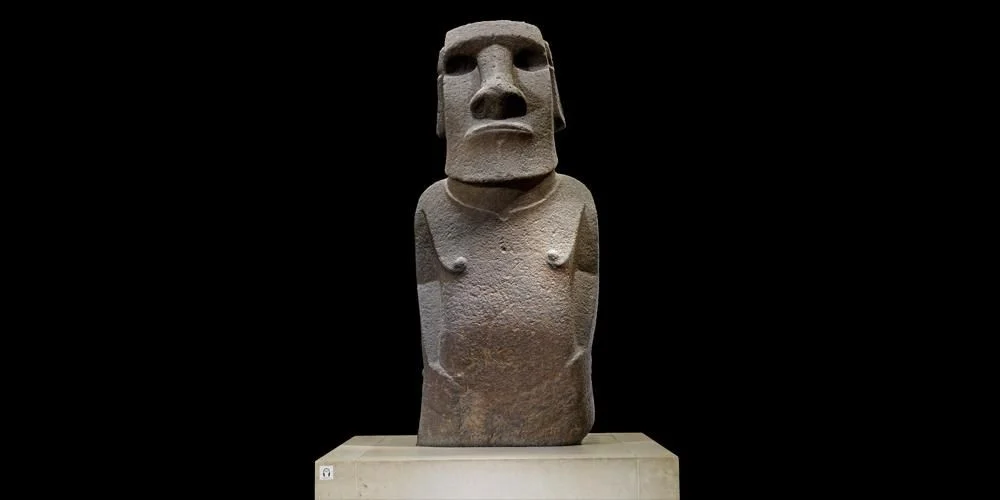

Rapa Nui sculptors

Carved around 1200 CE on Easter Island, this basalt moai, whose name means "lost or stolen friend," is a masterpiece of Rapa Nui culture. Taken in 1868, it features intricate back carvings from the birdman cult. Originally possessing red topknots and coral eyes, these figures were believed to channel spiritual power.

Yoruba sculptors, Kingdom of Ife

Cast in brass in the 14th-15th century, this naturalistic head from Ife (Nigeria) is a masterpiece of Yoruba art. Its delicate features and sophisticated casting technique challenged Western assumptions when discovered in 1938. Likely depicting an Ooni (king), it stands as one of Africa's greatest artistic achievements.

Ancient Egyptian embalmers

Dating to c. 1300-1280 BCE, this remarkably preserved mummy belonged to Katebet, a Chantress of Amun. Her elaborate cartonnage, adorned with gold leaf and vivid colors, depicts her in fine regalia. Scans reveal she died around age 35-40, and her burial offers an intimate glimpse into ancient Egyptian beliefs about immortality.

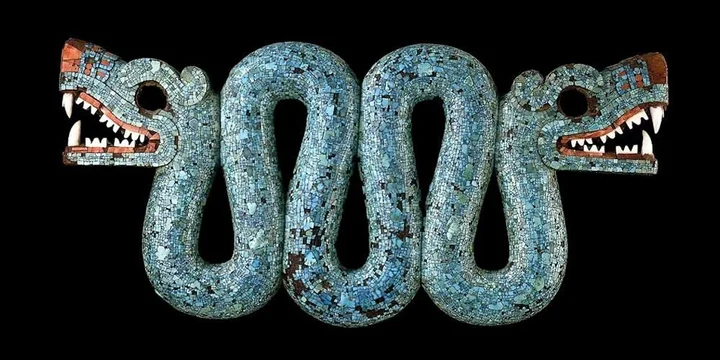

Aztec (Mexica) craftsmen

Created in 15th-16th century Mexico, this ceremonial ornament features over 2,000 turquoise pieces on a wooden base. The double-headed serpent, symbolizing duality, likely adorned a chest or staff. Possibly sent to Spain by Cortés, it is a rare surviving example of Aztec artistry, showcasing extraordinary craftsmanship.

Sumerian craftsmen

Dating to c. 2600-2400 BCE, this is one of the world's oldest board games. Found in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, the board is inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli. Its rules were deciphered from a later tablet, revealing a sophisticated pastime that remained popular across the Middle East for millennia.

Anglo-Saxon craftsmen

Buried c. 625 CE in a Suffolk ship grave, this iron helmet is the icon of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Likely belonging to King Rædwald, it blends British, Scandinavian, and Byzantine influences. Though found crushed, its reconstruction reveals an imposing face mask with dragon and bird motifs, symbolizing a sophisticated era.

Norwegian craftsmen

Carved from walrus ivory in 12th-century Norway and found in Scotland in 1831, these chess pieces are famous for their expressive, often humorous faces. Representing the Viking world's connection to the Islamic game of chess, they have become cultural icons, inspiring modern depictions like those in Harry Potter.

Want audio tours that actually make sense? We focus on the masterpieces that matter and tell you the stories behind them - no art history degree required.

This guide is written by Museums Made Easy, creators of museum audio tours for real visitors.

This guide is part of our museum highlight guides.

Browse all museum highlights →